A Life for our Times

The Gardener’s offering on his 152nd Birthday

Inviting all to have more than superficial knowledge of this incredible man…

UNIVERSAL MAN[1]

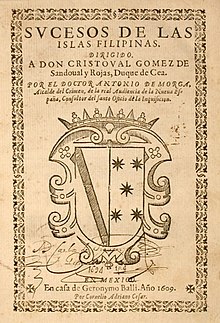

Apart from the Noli, the Fili, and the Soli, there was the Morga: yes, apart from his novels the Noli and the Fili and his articles in La Solidaridad, Rizal put out a new edition of the old Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas by Morga (surely pursuant to the objectives of his secret pact with Paciano), an edition now bristling with Rizal’s notes, explanations, expansions. The work of Morga, published in 1609 had enjoyed the fame among Spaniards and others as being the best account of the conquest of the Philippines. But in the time of Rizal, the work had become so rare that the few libraries that had a copy guarded it like an Inca treasure.

Activist scholar that he was, Rizal wanted to show to his fellows that before the Spanish advent, ours was a free, just, advanced and happy society. Our people were industrious and progressive, before they were conquered by Spain, but degenerated afterwards. “They lost their old traditions; they gave up their writing, their laws, in order to learn by rote other doctrines they did not understand, another morality, and aesthetics, different from their manner of thinking.”

For instance, Rizal made much of the fact that in his time people could no longer build boats as good as those built by his forebears. At every important point, he reinforced and elaborated Morga’s original picture of an idyllic society of honest freemen organized on the basis of kinship. Before the coming of the Spaniards, Rizal underscored with Morga, that not only were our people ship builders and cannon-founders; they exported silk to Japan and cotton to China; they made jars that the Chinese and the Japanese considered priceless, and they mined gold.

The ancient Filipinos, Morga noted, “wrote very well” in their own language and alphabet: under Spanish domination, most of them had become illiterate and education was discouraged. Now our people were being decimated in futile Spanish expeditions, making up the bulk of soldiers, sailors, galley-slaves, and auxiliaries of king-makers, fortune-hunters and missionaries. One cannot help but wonder if Rizal even so much as half-suspected that more than a century after his edition of Morga, most Filipinos would still not know their true history and origins. Today, despite all archives being open an impartial and complete history of the Philippines still begs to be written.

The ancient Filipinos, Morga noted, “wrote very well” in their own language and alphabet: under Spanish domination, most of them had become illiterate and education was discouraged. Now our people were being decimated in futile Spanish expeditions, making up the bulk of soldiers, sailors, galley-slaves, and auxiliaries of king-makers, fortune-hunters and missionaries. One cannot help but wonder if Rizal even so much as half-suspected that more than a century after his edition of Morga, most Filipinos would still not know their true history and origins. Today, despite all archives being open an impartial and complete history of the Philippines still begs to be written.

Innocent as a dove, wise as a serpent? Motives and tactics. It is well known that political exiles then as now tend to be mocked by the very people they fight for as being very brave and bold because out of reach. Was Rizal, like, perhaps, Ninoy a century later, killed by fatalism, by illusion, by amor propio, by the sneers and mockery of his countrymen, by his own pride? Of course, when martyrdom is done, the same people who were so cynical are also the first to say that we have one who was killed by patriotism.

For certain, Rizal was not one who could be said not to have exhausted all peaceful means and avenues. He did. With a new governor general at Malacanang (Despujol), he lost no time writing him, offering to cooperate with his government: “For good or ill, men have placed me at the head of the Philippine progressive movement and have attributed to me a certain influence on their aspirations. If your Excellency thinks that my lowly services could be of use in pointing out to him the country’s ills…I will place myself immediately at his command.” Sipsip (bootlicker)? But listen to the civil threat: “If this offer is rejected, my conscience will be clear; I have done all I ought, without ceasing to love my country’s good, to preserve her for Spain by means … of justice and community of interests.”

And if he was not all that welcome back in his own country, and given that his very family and town-mates, tested industrious farmers all, were being evicted from the land, why not allow him to take up the challenge in neighboring land-rich North Borneo, an ideal frontier near Mindanao where he could resettle the master farmers of his town to the mutual benefit of Spain and Britain? Wily Spain went by its age-old adage, piensa mal y acertaras (be suspicious to be certain), and saw in Rizal’s proposal not merely an agricultural development project but an ulterior plan to have a place outside but near the Philippines as a base for organizing and training the disgruntled and the dissident from all over the islands.

The Spaniards just may have had nightmares of Rizalians amassing arms and being trained to use them for lightning raids on the homeland, maybe in the style of their Moro brethren, till they were able to build a strong enough liberation army of invasion. No way, Jose! The Spanish authorities rejected the agricultural development proposal as mere cover to revolution.

In building a transformed people, Rizal had to engage in educational-organizational activities along certainly peaceful lines. The Liga Filipina was such an effort to establish a reformist organization. Even this, and especially this, the authorities could not, in political colonial conscience, accept. To them, if the North Borneo project were to mean raids from outside, the Liga would now mean raids from inside.

What did the Spanish authorities see in the Liga? They must have suspected what Andres Bonifacio may have clearly seen – that Rizal wanted to set something more dynamic in motion, beyond writing essays and publishing novels – engaging in people’s organizing and building at last the power of the people. In Rizal’s words: “We must win freedom by deserving it, by improving the mind and enhancing the dignity of the individual, loving what is just, good and great, to the point of dying for it. When a people reach these heights . . . the idols and tyrants fall like a house of cards and freedom shines in the first dawn.”

To the authorities and to Bonifacio, Rizal’s Liga was anything but peaceable, as they deduced from its aggressive charter, the first three rules of which read as follows: 1) unite the whole archipelago into a compact body, vigorous and homogeneous; 2) provide mutual protection in every difficulty and necessity; 3) provide defense against all violence and injustice. Is this not a revolutionary organization where duties of members are to obey blindly and punctually, to keep the strictest secrecy about itself, and not to submit themselves to any humiliation? Would not one therefore consider it as seeking to organize a government within the State by turning every Philippine community into a vigilante force?

The North Borneo development project proposal was an “I shall return” endeavor, or so it seemed to the authorities. The Liga project was certainly the more confrontational. It was an outline for the installation of People Power. If Rizal believed he could get away with either or both, then he truly underestimated his foes. In fact, he most probably did.

Never was his life happier than in Hong Kong in 1892 – a reputable practice, a popular clinic, financial stability, his family comfortable with him in good health and peace of mind, even some pretty girls to woo like the Irish schoolgirl (Josephine) at the Italian convent whose step father was his eye patient. But the long loneliness would not let him be. He was vulnerable to a trap. Provoke him by calling him a fake, comfortable warrior, who was covering up for his fear of going back home, and then make him believe the government had forgiven him and was giving in to his North Borneo proposal. It was an effective ruse. They convinced him to sail home. When he did, the Hong Kong consul’s cable to Malacanang read seriously: “The rat is in the trap.” It was, however, in a profound sense, a trap of his own making.

“I leave to expose myself to danger….to justify with my example what I have always preached,” wrote Rizal to his parents before he sailed for home. And in another letter for the Filipino people: “I know that my country’s future depends in some way on me….but my country still has many sons who can take my place. I want to show those who deny our patriotism that we know how to die for the sake of our duty and convictions.” His instructions were that these letters were to be published after his death. (Wasn’t Ninoy an avid Rizal reader? The Rizal-Ninoy parallelisms are quite a few.)

Capture, Trial, Execution

Charged, imprisoned, exiled. The charges against him were smuggling (having allegedly sneaked in the leaflets titled Pobres Frailes) and “disloyalty to Spain” (having published anti-Catholic tracts and dedicated his second novel to three “traitor” priests). He was brought to Dapitan, a jungle town in western Mindanao.

The Dapitan prison was happiness of sorts. It was a “prison” without walls. And it got Rizal to hunker down and become the development expert and expert businessman.

Four years in Dapitan saw the poet and literary man win the hearts of his “jailer” and the townspeople, lucky enough to win the second prize in the Manila lottery and buy 16 hectares of coastal farmland, set up a fantastic medical practice at socialized fees (no fees for the indigent, huge fees for foreigners who could afford), become a public works “director” and expert, providing the town with street lighting, constructing a reservoir to set up a water system, drained marshes to rid the town of endemic malaria, invented a machine that could manufacture 6000 bricks a day, modernized a town almost wholly of bamboo and nipa, engaged in scholarly researches in botany and zoology, become a veritable hacendero with a seaside farms in Talisay that expanded from 16 to more than 80 hectares devoted to corn, coffee, cacao, sugarcane and hemp, aside from thousands of coconut trees and hemp plants, modernizing agriculture and husbandry to the point of even importing farm machinery from the United States (!).

His hacienda did not only produce profits (selling his products in Manila for almost twice what they cost in Dapitan) but also sought to form prophets – youth whom Rizal trained on the job in his farms (which is how Dapitan got its first waterworks) and in the hacienda classrooms where he taught these live-in scholars Spanish, English, mathematics, geography, history and gymnastics. His school started with three pupils, increasing to 16 and eventually 21 in all. Classes were from 2 to 4 in the afternoon because mornings were for Rizal the physician, the agriculturist and the entrepreneur. Evenings he was a family man. Josephine had reappeared in his life.

How well did Rizal get to know the other parts of Mindanao, especially the Muslim population? Beautiful, so beautiful Mindanao made Rizal write Father Pastells that better than any holy book did the heavens declare the glory of God. When he was in leisure talks with Muslims did they not discuss the Inquisition and the wrongs of the Crusades?

Church and State probed Rizal in exile, his body and his soul. But he was one tough cookie. However, though so comfortable in Dapitan, he wanted out so urgently, again. When Europe promised him so promising a future, he opted to return east, where death bided. Snugly settled in Hong Kong, he insisted on moving to Manila, where death lurked. Now safely “imprisoned” in Dapitan, he was raring to go where death beckoned – the war in Cuba. Why?

His preeminence, the almost magical power of his name (Ninoy?), was established beyond doubt by Bonifacio’s angry resolve. Rizal was needed to make the Revolution; whether he liked it or not, they would make it; if, without him, in his name; but, if possible, with him, even as a captive leader.

And yet, had Rizal’s plan gone through, he would have been fighting for Spain at a time when his countrymen were fighting against Spain. Instead of our national hero he would have been our national villain.

He resisted the Katipunan’s offer to spring him from Dapitan because he had given his word not to escape. But did Rizal really say “No” to Pio Valenzuela of the Katipunan or merely “Not yet”? He advised Valenzuela to continue the work of recruiting, this time including the upper classes, to assure the uprising of a leadership from the ranks of the elite. Did he reveal, as alleged, the true reason for his return to the Philippines, namely, to procure funds and arms for a revolt? And did he really say to Valenzuela that he had already been promised three shiploads of armament by a Japanese official? And is it true that he explained why he had applied for army duty in Cuba, so he could study war in a practical way and have experience of it that he could use in the Philippines when the need arose?

He resisted the Katipunan’s offer to spring him from Dapitan because he had given his word not to escape. But did Rizal really say “No” to Pio Valenzuela of the Katipunan or merely “Not yet”? He advised Valenzuela to continue the work of recruiting, this time including the upper classes, to assure the uprising of a leadership from the ranks of the elite. Did he reveal, as alleged, the true reason for his return to the Philippines, namely, to procure funds and arms for a revolt? And did he really say to Valenzuela that he had already been promised three shiploads of armament by a Japanese official? And is it true that he explained why he had applied for army duty in Cuba, so he could study war in a practical way and have experience of it that he could use in the Philippines when the need arose?

In any case, time and destiny played their role tragically. Late in the day, Rizal’s application for Cuba was approved, the Katipunan was discovered and insurrection broke out, Rizal was put on board ship to Spain and from there to Cuba but was re-arrested to be sent back for trial in the Philippines. On the day after Christmas 1896, the trial was opened at the Cuartel de Espana. It was more of a hearing, an oral argument between opposing counsel, than a trial as generally understood, since no witnesses were called and cross-examined, no evidence submitted.

The legal issues in the Rizal case were not complicated. His propaganda activities in his books and other writings were patent. The prosecution argued simply: “In crimes of this nature, which are founded on rousing the passions of the people against the governmental powers, the main burden of guilt is on the man who awakens dormant feelings and raises false hopes for the future.”

The defense for its part said that Rizal had admitted to nothing but writing the statutes of the Liga where nothing illegal could be found, so that what remained was only “his life, his past works and writings, his previous record” as an agitator for reforms which were all known before the present insurrection. “Would any tribunal, with no other proof of guilt except that record, have condemned Rizal to death before the 19th August, before the events that are now taking place? Surely not.”

Nonetheless the court found Rizal guilty as charged and condemned him to death. The Governor General Polavieja ordered Rizal to be shot at seven o’clock in the morning of the 30th December in the field of Bagumbayan.

Moments before Rizal’s execution by a firing squad, the Spanish surgeon general requested to take his pulse – and found it normal. Aware of this, the Spanish sergeant in charge of the backup force hushed his squad to silence when they began raising “vivas” with the partisan crowd.

Rizal’s last words, ‘consummatum est’, Jesus’ own, prefigured in ways that he knew but could not exactly foresee, that his death would be the end of Spain in the Philippines, and the shot that the crowd heard that moment was the shot that brought Spanish Rule in the Philippines to an end

It marked as well the beginning of the end of all colonialism in Asia. Such was recognized by Mohandas K. Gandhi who regarded him as a forerunner and as a martyr in the cause of freedom. Nehru, in his prison letters to his daughter Indira, acknowledged his significant contributions in the Asian freedom movement.

Coinciding fortuitously with the age of Tagore and Sun Yat Sen, Rizal from an early age was enunciating in poems, tracts and plays, ideas all his own of modern nationhood as a practical possibility in Asia. In the body of written works for the period nothing compares to the outright statement in the ‘Noli’ that if European civilization had nothing better to offer, colonialism in Asia was doomed.

He stands among a few who belong to no particular epoch, who belong to the world, and whose life has a universal message. Although his field of action lay in politics, which he bore in the cause of duty–rendering him a rarity in human affairs, a leader without ambition and a revolutionary without hatred–his real interests lay in the arts and sciences, in literature and in his profession of medicine.

More than a hundred years after Rizal’s martyrdom, Malaysia’s former Deputy Prime Minister, Anwar Ibrahim, often quoted this line from the dedication in the Noli: “In the history of human suffering is a cancer so malignant that the least touch awakens such agonizing pains.” The dedication of the first Southeast Asian novel (according to Ibrahim) “stirred a critical awareness of the fundamental problems of colonial society. Its setting was the Spanish-ruled Philippines, but the book could have been about any nation in Asia.’”

Soon after his execution, the great Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno, in an impassioned and unforgettable utterance, recognized Rizal as one raised in the best traditions of Spain, “…profoundly and intimately Spanish, far more Spanish than those wretched men–forgive them, Lord, for they knew not what they did–those wretches who, over his still warm body, hurled like an insult heavenward that blasphemous cry, ‘Viva Espana’.”

When, much later, the Philippine Organic Act was being debated in the U.S. Congress, doubts about the capacity of Filipinos for self-government were swept away by a passionate speech of Congressman Henry Cooper of Wisconsin in which he recited an English translation of Rizal’s valedictory poem “Mi Ultimo Adios,” capped by a stirring peroration that underscored how a race that could produce a member of such talent and spirit had to be one most ready, indeed, for self-determination and self-governance.

Rizal’s life was all too brief in the space-time limits on the earth plane – so that going through the volumes written by him and about him one is struck by that quality so characteristic of him – indefatigability for the cause of his country. The debate between reform and revolution was, to him, a debate on means. More important to him was the goal, namely, the emergence of the Filipino nation with a glorious past that he had taken pains to point out in his annotations of Morga’s “Sucesos…”

Letters to Remember: The Ultimo Adios is well known. It is his last letter to the nation and to the world. On the morning of his execution, he dashed off a few more lines at 6:00 a. m.:

“My most beloved father, Forgive me the sorrow with which I repay the anxieties and toil you underwent to give me an education. I did not want this, nor expected it. Farewell, father, farewell!”

“To Paciano, Now that I am to die it is you that I write last to tell you how sorry I am to leave you alone in life, bearing all the burden of our family and our aged parents.”

“To my family,

I beg your forgiveness for the grief I cause you, but one day or another I had to die, and it is worth more to die today in the fullness of m faculties.

Dear parents, brother, sisters: give thanks to God who has kept me tranquil before my death. I die resigned, hoping that with my death they will leave you in peace. Ah, it is better to die than to live in suffering. Be consoled.

I commend you to forgive one another the little vexations of this life, and to try to live in peace and good harmony. Treat our aged parents as you would wish to be treated afterwards by your own children. Love them much, in memory of me.

Bury me in the earth; put a stone on top, and a cross. My name, the date of my birth, and that of my death. Nothing more. If you want to fence in my grave afterwards, you can do so. But no anniversary celebrations! I prefer Paang Bundok! [a common cemetery north of the city]

Pity poor Josephine.”

FINIS

[1] BOOK SOURCES FOR THIS ESSAY:

Nick Joaquin, Rizal in Saga (Philippine National Centennial Commission), Manila1996.

Leon Ma. Guerrero, The First Filipino (Guerrero Publishing with Anvil) Manila, 1998.

Fr. Jose Arcilla, SJ, Unknown Aspects of the Philippine Revolution (St Paul’s Philippines) Manila 2006