The Gardener’s Class starts the year-long celebration of the Fiftieth Foundation Anniversary of their Garden.

One of the Gardener’s classmates is now the Catholic Bishop of the Diocese of Sorsogon in the southern tip of Luzon. He was chosen to start off June 13th the remembrances of half a century of the Divine Word Seminary in Tagaytay by discussing the Catholic Church in her fifty years of Vatican II. Hereunder are some summaries of the hour-long dissertation of Bishop Arturo M. Bastes, SVD, DD.

“We were second year novices and first year philosophers then: part-time gardeners and amateur carpenters, feeling oh-so-far from the Manila we had left behind but whose lights we could see at night in the distance when we were not busy identifying the stars and constellations whose even sharper and brighter lights never failed to attract us, Astronomy students of Father Kalwey that we were.”

The Gardener’s class had each other; so, they did not mind being carted out to a “foreign land,” like dark and cold and very quiet Tagaytay seemed then, to physically and academically build a new school. They had their books and their teachers, excellent all in their various fields of expertise, and all classes talked of what was the latest, what was going on in the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council that had just opened the year before.

No, there were no cell phones and tablets then, digital technology was not even a thought, but there was Alitalia and Father Ralph.

Father Ralph Michael Wiltgen, SVD, an American missionary to New Guinea with a degree in Missiology from the Gregorian University, founded and directed the Vatican Council News Service, which published and dispatched twice-weekly news summaries in nine languages to more than 3,100 subscribers in 108 countries.

A cousin of one of the Gardener’s teachers had a special contact with Alitalia Airlines; so, the Tagaytay folk enjoyed “special delivery” of Father Ralph’s dispatches from Rome quite regularly, almost in “real time,” and they took turns reading them aloud in the dining room for all to chew their food over, in silence, till it was time to talk, and then discussions and sometimes debates would start in earnest, with quite a few pontificating about liberal this and conservative that, and what changes to expect and how it would all turn out in the end.

In sum, they felt like close-in witnesses to how the Rhine was flowing into the Tiber. Father Ralph’s interviews with hundreds of cardinals, bishops and theological experts made them feel like they were seeing the actions and hearing the actual words of the famous personalities of the Council – Cardinals Ottaviani, Frings, and Suenens; Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre; Fathers Karl Rahner, Joseph Ratzinger, Yves Congar, Henri de Lubac, John Courtney Murray and Hans Kung-and of course, Pope John XXIII and Pope Paul VI as well, to name a few.

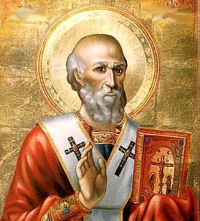

Pope John XXIII

The Gardener’s college class was a composite of seminarians who started High School in 1956 at the SVD-run seminaries in Quezon City, Cebu, Laoag, and Palo.

Pope Pius XII (Eugenio Pacelli) died on them when they were in second year high. He had been Pope before most of their class were even born. So, they got to know a different Pope early – John XXIII (Angelo Roncalli).

It did not take much to convince them that if the one who just died was of the aristocracy, this one coming in was of solid peasant stock, interestingly enough.

In any case, he was advanced in age and could thus be expected to take the role of transitional Pope. Nothing earth-shaking could or should possibly emanate from his papacy – by contrast with the lengthy one of the twelfth Pius who stood his ground in war and peace, infallibly defined the assumption body and soul into heaven of Mary, mother of Jesus, and issued the encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu that firmly set Catholicism in the path of biblical scholarship.

Whoever would have thought or even slightly suspected that we had in Pope John a man who could divide all modern ecclesial time into two epochs: pre- and post-Vatican II? Perhaps not even Pope John himself did. Not since Pope Alexander VI (Borgia) who divided the world into two – one part for the Spaniards and the other part for the Portuguese did any other one do anything like this.

Less than three months after his October 1958 coronation as Pope (yes,

friends: “coronation”), John XXIII – on 25 January 1959 gave notice of his intention to convene an ecumenical council.

It was a clearly inspired sudden announcement which caught the Curia by surprise, caused little initial official comment from Church insiders but elicited widespread and largely positive reaction from both religious and secular leaders outside the Catholic Church including many who hardly understood what an ecumenical council was all about but slightly suspected that this could usher in revolutionary changes within this age-old powerful world institution.

Actually, a few days earlier, on January 20, 1959, Pope John already intimated to his secretary of state, Domenico Cardinal Tardini that “in response to an inner voice that arose from a kind of heavenly inspiration” he felt “the time was ripe” for him “to give the Catholic Church and the whole human family the gift of a new ecumenical council.”

Giovanni Cardinal Montini, who later became Pope Paul VI, is said to have remarked to a friend that “this holy old boy doesn’t realise what a hornet’s nest he’s stirring up.”

It was fewer than ninety years after the First Vatican Council. The latter’s predecessor, the Council of Trent, had been held much, much earlier – centuries earlier – in the 16th century. No wonder Pope John’s announcement quickly became grist for the curious journalistic mills of the mid-point of the twentieth century. Something historic was afoot.

The First Vatican Council had been cut short when the Italian Army entered the city of Rome at the end of the unification of Italy. On paper, that council lasted only briefly, from 1870-71. As a result, only deliberations on the role of the Papacy and the congruent relationship of faith and reason were completed. An examination of pastoral issues concerning the direction of the Church was left unaddressed.

And, interesting to note: technically, that brief Council had never been suspended; it had never ended because the Italian troops marched on Rome while it was in session and it had to break up unadjourned. In fact, one of the first things Vatican II did when it first met was to adjourn Vatican I which, technically, was still going on except that not one of its members remained embodied and visible; all were present only in spirit, invisibly – a fact that was no big deal for a Church that intensely believed in the communion of saints. One could only surmise, though, whether, for instance, the great John Henry Cardinal Newman (later beatified, that is, proclaimed “Blessed” by Pope John Paul II) was still objecting to the doctrine of papal infallibility as he did before the Council was so unceremoniously interrupted by the Italian army.

The Gardener’s class was now in second year college at Christ the King Mission Seminary in Quezon City when the Second Vatican ecumenical council was formally summoned by the apostolic constitution Humanae Salutis – on Christmas Day 1961 (so, Pope John was really thinking of a gift, a Christmas gift to church and humanity). It is most interesting to know, if one could, what really went on in the mind of Pope John or, if you will, how God the Holy Spirit was inspiring him on. In referring to his council idea he often said that “it was time to open the windows of the Church to let in some fresh air.” Wasn’t he also thinking not just of air but of the Wind that breathes where it wills – sometimes even from the “world” to the “Church” and not just always the other way around?

There had been some speculation that this council would include at last more than just bishops and heads of male religious orders. One reason why general councils had been held with some caution, if not suspicion, by modern Popes was because in the Council prior to Vatican I there had been a movement to resolve the difficulties of the age (the sixteenth century) by proposing to allow Martin Luther and his followers to participate on a basis of equality with those who were in communion with the Holy See, which clearly the Holy See found totally unacceptable.

Pope John, for his part at this time, gave out invitations which were accepted by successors of that 16th century movement – Christians outside the Catholic Church, both the Protestant denominations and Eastern Orthodox churches, to send observers to the Council. The world got quite excited even with the mere possibility of having Catholics, Protestants and Orthodox Christians get together at last in one way or another as “one fold under one Shepherd.”

Pope John spoke of two “spectacles” (developments) in the post-war society that spurred him into action: the growth of materialism and unbelief in the secular world and the rise of a new confidence in the Christian community.

In response to these developments, he said, he would call a synod for the leaders of the diocese of Rome, revise and update the Code of Canon Law, and summon an ecumenical council. The Italian word he used to characterize the canon law project — aggiornamento (updating) — soon became the unofficial motto for the larger project of the council too.

A New Style

For centuries, the Catholic style in its search for truth had been dominated by a near-obsession with rebuking enemies of the faith.

“If anybody says otherwise, anathema sit.” (Let him go to hell!)

Did not the Church on the earth plane style itself as the Church Militant? So it was. In this style what Catholics stood against — what was anathema – was often clearer than what they stood for and what they should yearn for in their moral and spiritual life. In documents like the 1864 Syllabus of Errors, church authorities issued sweeping condemnations of freethinking ideas that challenged the laws and social norms laid down by popes and bishops. Galileo was far from the only voice silenced by cavalier church disciplinary action down the centuries. One need not mention the Inquisition to make the point.

Much, much earlier, of course, in the first centuries of ecumenical councils the debates over one phrase alone, or one word alone, or even one dot alone were enough to cause so much verbal and physical violence and even wars and schisms among peoples who all professed to follow Jesus.

“Do you believe that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son (filioque) or do you believe that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son (per filium)?” Two camps, irreconcilable, led to centuries of terrible division –was all this for real?

Or take the protracted wars between those who followed Athanasius and those who followed Arius. It seemed like merely a question of the correct spelling and pronunciation: “do you subscribe to homo ousia or to homoi ousia – of the same substance or of similar substance?”

Perhaps, those struggles had to come about. They surely were the stuff of Church history and ultimately gave Catholics the quintessence of their Creed. This new Pope, however, was of a different mental bent. He said: “What is needed at the

present time is a new enthusiasm, a new joy and serenity of mind in the unreserved acceptance by all of the entire Christian faith, without forfeiting that accuracy and precision in its presentation which characterized the proceedings of the Council of Trent and the First Vatican Council.

“What is needed, and what everyone imbued with a truly Christian, Catholic and apostolic spirit craves today, is that this doctrine shall be more widely known, more deeply understood, and more penetrating in its effects on men’s moral lives.

“What is needed is that this certain and immutable doctrine, to which the faithful owe obedience, be studied afresh and reformulated in contemporary terms. For this deposit of faith, or truths which are contained in our time-honoured teaching is one thing; the manner in which these truths are set forth (with their meaning preserved intact) is something else.”

Although from these words of Pope John it was clear that Vatican II would have to maintain continuity with previous councils, it would nonetheless be unique in many ways. For one, the style was invitational and pastoral.

Unlike previous councils which used technical, juridical and punitive language, Pope John himself told the council to offer the modern world the “medicine of mercy rather than that of severity,” and to demonstrate the validity of Church teachings rather than the terror of Church condemnations.

Unlike previous councils, Vatican II should seek to use words of respect instead of anathemas and excommunications; it addressed all as sisters and brothers and men and women of goodwill. It was the style of the early Fathers of the Church, who patiently relied on the art of persuasion and finding common ground. It was not the style of fear. It was the style of charity above all. It was all beginning to sound very Christian at last, – didn’t it?

What then did Vatican II do?

Vatican II

Vatican II gathered some 2,625 Council Fathers from all over the world who held four sessions, each approximately three months long, in the years 1962-65.Their output was hefty: sixteen ecclesiastical documents, written by teams of several thousand bishops and theologians, based on three years of preparation and four years of prayer and discussion.

A decision was made before the first document was written that the audience or readership, to which their documents were addressed, would not just be academics and clergy. Therefore, the vocabulary of the documents was to be biblical, not scholastic; the style was to be pastoral, not academic – in order that the council’s teaching would be accessible to all literate Christians, and, indeed, all people of good will.

This did not mean that the Council would be “anti-intellectual” at all. On the last day, in fact, of the Second Vatican Council, December 8, 1965, as part of the council’s final pageantry and symbolic conclusion, messages were addressed by Pope Paul VI and the bishops to several groups representative of those segments of the cultural world that the council most hoped to engage. Jacques Maritain, perhaps the greatest Catholic philosopher of the 20th century, was asked to accept the message for “thinkers and academics” (“les hommes de la pensée et de la science”). Not only had Maritain influenced the council in matters like religious liberty and human rights, but he represented the kind of echo ascribed to Augustine: “Let us seek with the desire to find, and find with the desire to seek still more.”

The Council created three classes of documents: the most important and generally longer are called Constitutions–of which there are four. There are nine “middle-distance” documents, so to speak, which are called Decrees. And finally three brief documents narrowly focused in theme are called Declarations.

(to be continued)